Last Updated on January 18, 2024 by Greg Gillson

|

|

Backwards bending knee? Nope. That joint is the heel, not the knee!

Greater Yellowlegs

Photo by Greg Gillson

|

Do bird’s legs bend backwards compared to human legs? No.

Bird’s legs and knees don’t bend backwards. Bird’s legs and knees bend in the same way as yours and mine.

Even though they may know better, many bird watchers still call the backward facing leg joint on long-legged birds “knees.” But that is not correct.

Birds walk on their toes. The long lower bone attached to the toes is really the foot. That backward facing joint would be the heel and ankle for you and me.

That long leg bone that disappears forward into the bird’s plumage? That is the tibiotarsus, the “drumstick” with tibia and fibula bones and the fat calf muscle on the upper end at the knee. Connecting to the real knee on the end of the drumstick under the feathers is a short stout femur or thigh bone. It connects to the hip near the base of the tail up on the back.

Birds, like cats and dogs, are digitigrade

Digitigrade, as you may remember from high school biology, is when an animal walks on its toes.

People are plantigrade, walking with the heel on the ground.

The other option used by deer, cows and horses is unguligrade. These animals walk on their toe nails which are hooves.

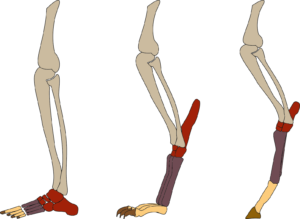

Whether a giraffe, mouse, sparrow, or human, all the leg bones are there, just longer or shorter or sometimes fused together. But the number of toes varies from 1 to 5.

|

|

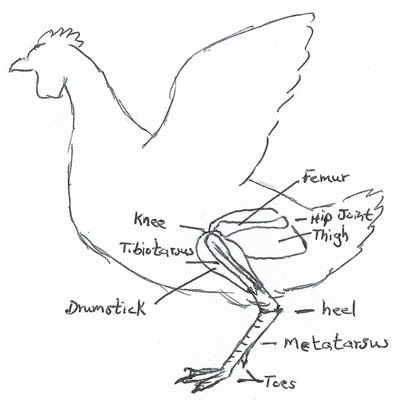

Chicken legs and feet

Sketch by Greg Gillson

|

Some anatomy

So far in this discussion I haven’t been very accurate in my terminology, using rather inaccurate common terms to relate bird anatomy to human anatomy.

Using the sketch I made of the chicken (above) we’ll start at the toes and work our way up to the hip with the scientific terms. For this I reference Ornithology in Laboratory and Field (Fourth Edition). 1970. Olin Sewall Pettingill, Jr.

Birds have 4 toes (some birds only 3, Ostrich 2). On a chicken three toes point forward and one is behind. The hind toe is the hallux (toe #1) and is equivalent to the big toe of humans. The hallux can be incumbent, that is, on the same level as the other toes. The hallux of the chicken, though, is elevated, the tip not reaching the ground.

Each toe is made up of phalanges: bones that help the toe bend. Each toe ends with a curved claw. The hallux has 2 phalanges, bending in one place only. The inner toe has 3 phalanges, bending in 2 places. The middle of the forward toes has 4 phalanges, bending in 3 places. The outer toe has 5 phalanges, bending in 4 places. That is quite different from human toes!

The long lower leg bone of a bird is actually the foot, or what would be the instep in humans. It is a single bone, the metatarsus, composed of what would be some ankle bones and 3 foot bones leading to each toe. At the toe joint the three-bones-in-one separate enough to be seen at the knuckle.

Okay, we’ve reached the drumstick, the “real” lower leg bone. In humans the two lower leg bones are the tibia and fibula. In birds, however, some of the ankle bones (tarsals) are fused with the tibia, forming the main heavy bone called the tibiotarsus. The thin fibula extends only 2/3 of the way down the leg and does not reach the ankle.

There is a small patella, or knee cap. Yes, birds have kneecaps!

The upper leg bone is the femur. It connects to the tibiotarsus at one end and the hip socket at the upper end. This is the thigh of the chicken.

Okay, from now on I expect you to have very interesting dinner conversations every time you have fried chicken!

The length of the various bones vary quite a bit in birds. Long-legged flamingos and short-legged hummingbirds are about as opposite as could be. Yet the bones are all there, if quite different in size and length.

Did I cover everything? I guess there’s no need for you to see how this arrangement varies with your dog, whose hind leg is more similar to a bird’s leg than your own. That “dogleg” is the heel. The knee is higher up and forward and, like a bird and a human, points forward in the same manner.

Wrapping Up

Another fascinating question often asked about birds’ knees is Do penguins even have knees?.

Well, penguins do indeed have knees! It’s a common misconception that their short, plump legs and waddling gait mean they lack this crucial joint. However, look beyond the feathers and you’ll find the same four bones that make up your own knee: femur, tibia, fibula, and patella (kneecap).

Here’s the evidence:

1. X-rays: X-ray images of penguins clearly reveal the presence of a knee joint, with all four bones mentioned above positioned similarly to those in humans and other mammals.

2. Anatomy and movement: While the feathers and thick layer of muscle make the knee joint less visible externally, careful observation reveals subtle movements that hint at its presence. Penguins can flex and extend their legs, which wouldn’t be possible without a knee joint.

3. Evolution: Penguins evolved from flying birds, who possess knees essential for locomotion. During their transition to swimming and walking on land, penguins adapted their knee joint for different functions while retaining its basic structure.

4. Fossil evidence: Fossils of prehistoric penguins, like the early Eocene genus Palaeopteryx, show similar leg structures with a distinct knee joint, further supporting its presence in modern penguins.

So, the next time you see a penguin waddle, remember that those plump legs are more complex than they seem. Beneath the feathers lies a hidden wonder of nature – a fully functional knee joint that allows these amazing birds to thrive in their unique aquatic and terrestrial environments.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do birds have knees or elbows?

Birds do have knees and elbows, although they may not look exactly like their human counterparts! Here’s the breakdown:

Elbows:

Birds have a joint in their wing that functions similarly to an elbow, allowing them to bend and fold their wings for flight and other movements.

However, this “elbow” is actually formed by a different set of bones than the human elbow. In birds, it’s created by the junction of the humerus (upper arm bone) and the radius and ulna (forearm bones).

Knees:

Birds also have knees, located in the lower leg where the femur (thigh bone) meets the tibiotarsus (shin bone) and fibula (smaller leg bone).

Interestingly, the bird knee joint actually bends in the opposite direction of a human knee! So, when a bird bends its leg, the “knee” appears to be pointing backward. This adaptation allows birds to walk and stand on their toes, giving them better balance and agility.

The difference in bone structures and bending directions can lead to confusion about whether birds have true knees and elbows. Additionally, the feathers and musculature around these joints in birds can make them less visible compared to humans, further contributing to the misconception.

Do birds have knee caps?

Not all birds have kneecaps, but some do! It’s a bit more nuanced than a simple yes or no answer. Here’s the breakdown:

Some species, like ostriches, have a double kneecap! This unique feature is likely an adaptation for supporting their massive weight and powerful running speed.

Many birds have a single kneecap (patella), similar to humans, but it might be less prominent or even embedded within the tendon. Examples include hawks, ducks, and crows.

Some bird species lack a kneecap altogether. This is often seen in smaller birds and those with simpler leg structures, where other adaptations offer sufficient support and flexibility. Examples include sparrows, hummingbirds, and some waders.

What kind of bird is called thick knee?

“Thick-knee” isn’t just one specific bird, but rather a common name used for a group of ground-dwelling birds within the family Burhinidae. These fascinating birds are found in tropical and temperate regions around the world, with most species occurring in Africa, Asia, and Australia.

Here’s some information about these “thick-kneed” birds:

- Medium-sized, typically ranging from 30-60 cm in length.

- Long, strong legs and thick knees (hence the name!)

- Cryptic plumage often in shades of brown, buff, and gray, allowing them to blend in with their surroundings.

- Large, yellow eyes that give them a reptilian appearance.

- Strong, pointed bills for foraging on insects and small animals.

- Mostly nocturnal or crepuscular, meaning they’re active at dawn and dusk.

There are 10 species within the Burhinidae family, each with its own specific name.

Cool. Who knew.

Thankz